He thought the stamp went in the upper left-hand corner of the envelope.

An actual letter, written in pen on paper and mailed to a street address with a postage stamp, may seem a relic of the past to college students, digital natives that they are.

So, a freshman can be forgiven if he doesn’t know what corner of the envelope takes the stamp – or even how much a stamp costs. And yes, that really happened.

In the First-Year Seminar course that examined Mary Shelley’s epistolary novel “Frankenstein,” Raymond Boisvert, Ph.D., asked students to send an actual snail mail letter (cards didn’t count) to a friend or family member and get their reaction. The next step was to interview their recipient about letter writing in general – what part it played or still plays in their lives.

Boisvert said he wanted to impart the importance of letters, not only in the novel but in people’s lives throughout the centuries - the emotion and detail that can be conveyed, the unique handwriting, the patience needed to wait for a reply, and the time factor that needs to be considered when sharing or waiting for news.

“Letters now take a couple days to get to their destination through the postal service,” he said. “During the late 1700s, when ‘Frankenstein’ is set, letters could take weeks or even months to get where they were going.”

Most of the FYS students worked with their grandparents for the project. After all, they are from a generation with years of experience in putting words to paper to communicate over long distances. They know well the emotion that can be conveyed in a letter, which is physically touched by both writer and receiver.

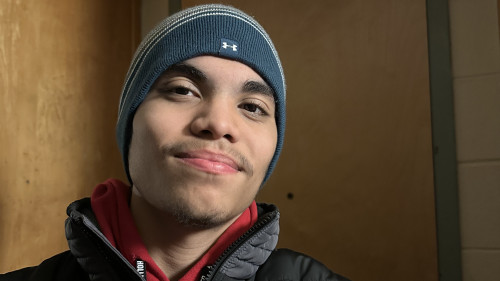

Eric LaPointe ’21 said his grandmother has saved letters from decades ago from his grandfather, from his time in Texas training to be on the border patrol.

Marcella DeAngelis ’21 said her grandmother occasionally drops her a line at Siena, asking if she wants to come over for Sunday dinner.

One of the few to write to someone of her generation was Deirdre Kokasko ’21. She wrote to a high school friend during his first summer at the U.S. Naval Academy - electronic communication wasn’t an option for him, as plebes are only allowed to receive handwritten mail during their early weeks at Annapolis.

“He and I talked about why letter writing is important, about how it helps make true connections, and how it can accomplish this better than a text or e-mail,” said Kokasko.

One student said her grandfather keeps a stash of old love letters — not all of them from the woman he eventually married.

“They’re in a place no one else knows about,” she said.

The student is now the only one besides her grandfather who knows the hiding place – or that the letters even exist.

Boisvert collected the letters the students had written and mailed them himself from campus (that’s when he noticed the misplaced stamp) so that they all went out on the same day.

“A few had experience writing a letter or two, but most did not,” he said. “I was surprised that the most important letter they had received in their lives so far was their college acceptance letter.”

He noted the emotion tied to handwritten letters, evidenced by the fact that many of those interviewed for the project had kept some letters for decades.

“How will today’s students be able to truly express their love and feelings to people through e-mails or texts?” Boisvert wondered.

Even though Gen Z have little life experience with the postal service, the desire to get some mail that isn’t electronic still burns as brightly as it did for generations past.

“I stop by my mailbox in the student union every day on the one percent chance I might get a letter or something,” said Aerin Bacon ’21. “I never do.”