We see the lovely handcrafted items at fair trade markets – colorful scarves and table runners, felt slippers and toys, baskets, and more. We buy them because they are practical and pretty, and because they support the families of the Central American artisans who make them.

But are these women – and they are all women – really earning enough from sales to improve their lives? A Siena professor and her student recently traveled to Guatemala to find out.

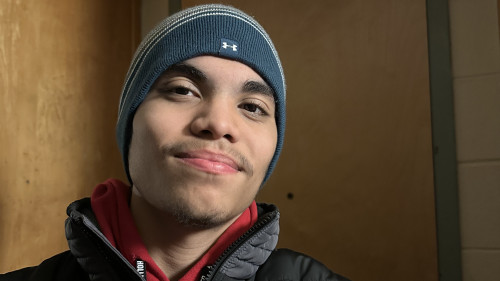

Vera Eccarius-Kelly, Ph.D., professor of comparative politics, and Billy Mayer ’18, went to the Central American nation in February to interview the artisans about their fair trade work and how it has impacted their households and communities. Mayan Hands, an Albany-based collective that employs all the women interviewed for this effort, organized the survey of 160 women. This portion of the survey was Mayer’s senior capstone project, and the results are looking positive for everyone involved.

Mayer, a political science/Spanish double major from Kings Park, N.Y., and Eccarius-Kelly were obtaining more detailed answers to baseline information on the women’s home needs, earnings, access to services, and more. The women employed by Mayan Hands are indigenous to the Guatemalan Highlands, the poorest of the poor.

“The purpose is to test whether fair trade truly delivers on its commitment to improve the standard of living for the women who are employed,” she said. “We are looking for hard data and observations to confirm that family incomes are indeed increasing, that no child labor is being used, that the families have access to education and health care, and that the women are becoming increasingly independent.”

Professor and student were aided by field workers, as some of the artisans spoke only indigenous languages. They met the workers at the homes of each crafting community’s elected leader. When they were able to see the homes, they were able to see the working electricity, the water filters and the extra livestock purchased with the money the women earned.

The majority of the surveys have been completed, and are currently being analyzed with the help of special software designed for political scientists.

“The more detail we could get, the better,” said Mayer. “The women were very happy to meet us and were excited to tell us about their lives. They deal with hardship but were very matter of fact about it. ‘It’s just my life,’ one woman said.”

The crafts created by the women range from $5 friendship bracelets to multicolored raffia and pine needle baskets so expertly made they are sold in the Smithsonian Institution gift shop in Washington, D.C.

Eccarius-Kelly said another chief goal of the fair trade movement is to regularize household income. Once the women know they have a steady source of income, they can budget for their extended families, including school tuition, heath care, home improvements and more.

“Economically, each woman’s success impacts the lives of 20 other people,” said Eccarius-Kelly.

After the survey data is compiled and analyzed by this spring, Eccarius-Kelly and Mayer will make recommendations to Mayan Hands about specific issues that need to be addressed going forward, and they will publish a paper together later this year. Mayer will also present at the National Conference for Undergraduate Research in Oklahoma this April. Several other Siena students will be attending to present their topics.

“This is the kind of experience Siena students receive that you would never get anywhere else,” said Mayer. “Conducting joint research with a professor, presenting at an academic conference, getting published – I’m very grateful for the opportunity.”